Haymaking

The only time I ever saw my Grandad buy alcohol was for haymaking. As the summer days became hotter and dryer, inside the larder would appear a large bottle of Woodpecker Cider, in it’s distinctive green and red livery.

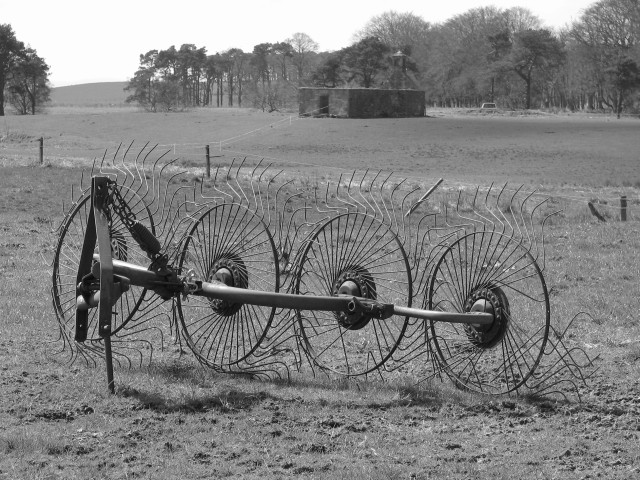

The grass had been mown a while ago and it was a common sight to see Grandad crossing the fields in the little Ford tractor with the acrobat behind. Four yellow wire Catherine wheels turning in slow synchronisation as he chugged along, picking up the drying stems and fluffing them up, turning them over to ensure an even bake in the hot sunlight.

Eventually the rows would be brought together. Long ribbons of sweet smelling stems wound themselves across the shorn turf. I ran around them, vaulted over, dived in. All of this was there to play with until baling.

Out would come the rusting red New Holland baler. Most implements were rusting. Buying anything new was strictly avoided. The baler would be hooked up to the tractor and power sent down through the PTO, the rotating shaft barely covered with it’s slightly broken yellow safety guard.

Now a baler is a complicated beast. Essentially, all it has to do is to pick up loose hay from the ground, squash it into an oblong like a giant lego brick, tie some twine around the bale to hold it together and then spit it out the back, ready to be collected. But to ready the machine for this seemingly easy task involved a lot of head scratching, prodding, tightening, oiling and the occasional lump hammer. You see, there were so many variables to consider. How fluffy was the hay? How dry was it? How fast was the tractor to drive? What type of baler twine was in use?

The process of making each bale involved some form of arm, deep inside the baler, that pounded the loose hay along a slider into the space that moulded it. As the machine was running, a distinctive, slow, 'thud, thud, thud' would be heard. And the timing and aggression of the thud, was the essence of a good or bad bale. Too soft and the bales would fall apart once spat out the back. Too hard and they would be heavy, hard to move and might burst or the hay be smashed into bits.

Likewise, the twine (you never called it string, unless you wanted to sound like a townie) had to be not too tight or too loose.

After the annual trial and error to get the old machine running spick and span, it would then be unleashed onto the rows of waiting hay. Soon, the field would be littered with bales. Golden green lumps of summer, ready to be collected and stored for winter’s dark and cold.

If we were lucky, the hay would have been baled in a field far away from the farm, preferably really far away and in a location that would take us past our friends' houses, the village and the people we knew. Because, on this little farm, collecting in the hay was a manual task, done with hands, sweat and pitchforks. And for a manual task you needed man or men. And even as boys, my brother and I were expected to help. We would help stack the bales onto a flat wooden trailer. Linking them together in a mosaic pattern so that they supported each other and locked each other together as the trailer load became higher. Eventually when it was about 12 feet high, a rope would be thrown over the top, front to back to hold the gigantic bundle together whilst the harvest was hauled home. And this was the moment that I looked forward to most of all, and it is the reason why I wanted the fields to be as far away as possible and on a route that took me past friends and houses and the community.

You see, to get back, my brother and I would have to ride back. We would have to climb to the top of the hay cart and sit right on top, holding onto the rope to stop us falling off as the trailer lurched and swayed. Occasionally we would need to duck as low tree branches threatened to sweep us off onto the ground. But more important, most important of all was that on the way back, I really wanted my friends and people from the village to see me, me on top of the hay, me a man doing man work, me looking down on the world below from my high point. The ride on the hay cart was the stuff of boys adventure. And I wanted everyone to see me riding.

Once we’d arrived back at the barn the haystack would be created. From nothing, a small pile of bales would grow taller and taller. Each returning trailer bringing more bale ‘bricks’ to build the stack. To begin with it was easy, just picking the bales off the trailer and placing them where required. But then as it grew, pitchforks or prongs (as they’re called in Sussex) would be used to fling them higher. Eventually even this was impossible, once the stack was higher than a man’s reach. At this point the elevator would be required.

By now, it wasn’t just us boys who were joining in the haymaking. A number of men, who’d helped my grandad over the years would somehow appear and assist to bring everything in. The first I would see of them would be a group standing round the elevator trying to coax it into life (similarly to getting the baler running)

This ‘elevator’ was a Lister. Lister was an old brand of farm machinery and it’s name was proudly displayed on the side. It consisted of a spindly frame with four tiny wheels, most of which had lost their tires. On top of the frame was a long, wooden slatted conveyor driven by rusting square linked metal chains. Sat in the middle of this steel skeleton was an old diesel engine usually covered in an oily sack over the winter. It would take about an hour to bring her to life amidst cleaning of spark plugs, filling with oil, prods, pulls, tweaks, splutters. But eventually she would roar into life through her broken exhaust pipe and fill the air with blue diesel smoke.

Levers would be pulled, rusty joints would creak and scream and them slowly live again. The belt would begin to turn and the wooden slats of the conveyor would start to wind upwards. A few more adjustments to raise the top of the Lister. More to drop the bottom down to match the trailer and top of the stack. Then work began again, only at a faster pace.

My job would often be to load up the elevator. Lining up bales onto the slats, so that they could begin to tug them upwards. Making sure they were on straight, before further adjustments became impossible as the bale inched away. I’d watch each one climb along the Lister’s back until it reached the top. Here it had to be grabbed by one of the men standing at the top, before it fell off forwards and caused a jam.

Amidst the team we would be encouraged to work faster. Although only children, my brother and me wanted to be one of the men, the team, so we lapped up the praise and broke a sweat lifting, humping and delivering bales to the waiting hands above.

There would be a time when the last bale had been slotted into it’s rightful place. By now the hay stack was so high that it touched the top of the barn roof, a good 20 or 30 feet in the air. It radiated warmth as if made from the sun's rays. Sweaty and tired, the men (and boys) would come down off ladders and talk about the day's work done well. Grandad would disappear into the house.

He’d come back with the cider and glasses for all. Pouring out the amber liquid to thank each workman for their effort in bringing in the harvest. Us boys were not usually given the cider, we would have orange squash instead.

But this day, my grandad turned and looked at me, gave me a glass, and smiling, poured out a measure of cider. I may not have been a teenager yet, but in that group, I was now a man.

photo: Callum Black / Old hay rake /